‘Beneficiary’—A Loaded Word

“Beneficiary” isn’t just outdated; it’s paternalistic. It implies that support is something “given” to people rather than something they actively engage in. This term reinforces a hierarchy where power remains with the organization, not the individuals themselves. Despite claims of empowerment, “beneficiary” feels like a relic from an era when those in need had no say, and assistance was something bestowed from a distance.

Why ‘Client’ is My Preferred Alternative

One alternative I lean toward is “client.” Some may find it cold, but I see it differently. Calling someone a client lifts them up—it places them on equal footing. In social work, “client” is a common term precisely because it’s neutral and respectful, implying that the person has rights and is entitled to quality service. It acknowledges that those we work with aren’t passive recipients; they’re people with agency, preferences, and dignity.

Another option is “people we work with.” Although it’s an improvement, it still feels hierarchically. “The people who work with us” is closer to the partnership I envision. It suggests a future where communities can choose the organization they work with, just like a customer chooses a service provider. The distinction might seem small, but language shapes perception.

However, in practical contexts, such as when working with tables or reports to number the scope of a project, using terms like “people we work with” may not be feasible. In such cases, “client” again emerges as a better alternative to the b-word.

Enough with the ‘Humanitarian Zoo’

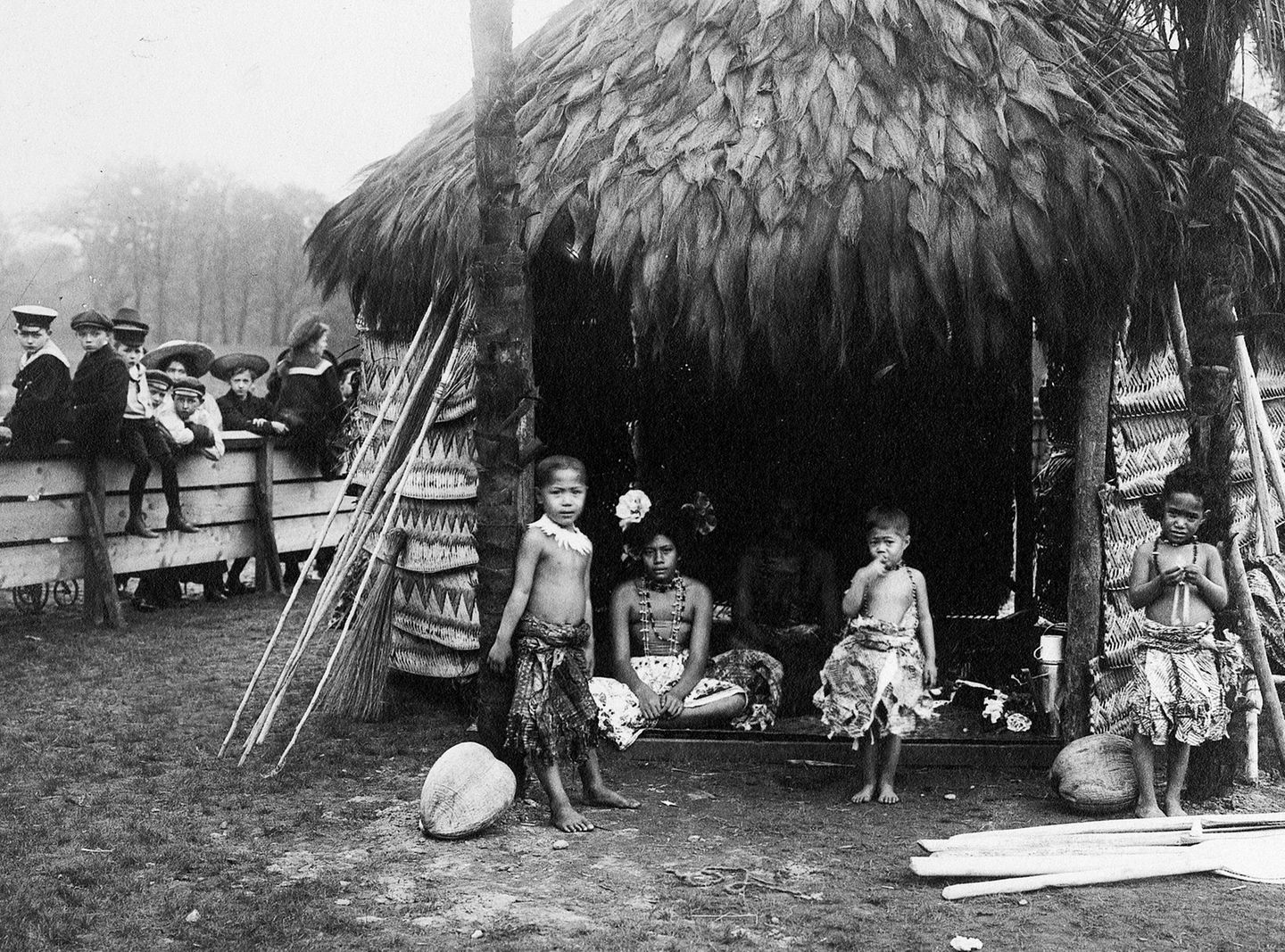

Let’s talk about the images we use. Seeing pictures of smiling children or struggling families used in fundraising materials has always unsettled me. Turning people’s struggles into a spectacle to generate sympathy and donations. This approach fuels a voyeuristic curiosity. It’s reminiscent of the “human zoos” of the 19th and 20th century, like those in Hamburg’s Tierpark Hagenbeck, where people were put on display for being “exotic” or “different.” Unfortunately, some modern NGO imagery isn’t far from this.

And let’s be real: No one in the Global North would consent to being displayed this way if they and their children were depending on government assistance. Social service institutions on social media never feature identifiable clients; instead, they anonymize faces—pixelating eyes or using angles that preserve privacy. Why is it acceptable elsewhere? Over-exposed depictions of children in vulnerable contexts—whether smiling while drinking water or receiving medical treatment—can have profound and lasting effects on their self-identity as individual persons. These portrayals not only shape how they are seen by others but also shape their very view of themselves, normalizing the narrative of being different and being dependent. Please, start treating others as equals.

Consent Isn’t a Free Pass

Some might argue that people give consent for their images to be used. But let’s look at reality. When someone is dependent on an organization for basic necessities, is that consent truly free? Is it really an informed choice? Do they really understand where, for which audience, and for how long their face will be displayed—or have any control over it? Or are they, in that moment of vulnerability, simply agreeing to anything to secure the help they need? Signing a consent form doesn’t erase the complex power dynamics at play. And frankly, asking for it in the first place feels exploitative.

Shared Needs and Dreams for a Dignified Life

At the core, people in need have the same essential needs and dreams as anyone else. Whether in rural villages or urban centers, people everywhere seek dignity, security, and connection. They want to feel loved, respected, and connected through meaningful relationships. They seek opportunities to learn, grow, and create better lives for their families. Yet, these universal aspirations are often overshadowed by portrayals that reduce individuals to stereotypes, stripping away their humanity and individuality. In our public communications, embracing this shared humanity as a given allows us to move beyond depicting people solely as “different and deprived.”

What We Should Be Showing Instead

There’s a better way forward. Rather than exposing clients, we should highlight the talented professionals within our organizations—their expertise, reflections, and calls to action. These practitioners can credibly tell us what is needed to enhance their work and amplify their impact.

Shifting the focus from the individual hardships of clients to the expertise of practitioners provides a perspective that is clear and actionable. This approach fosters meaningful progress, respects the privacy of those we support, and engages donors through a shared commitment to equality and humanity—upholding our mission to do no harm.